DIE GENTECHNIK ALS SPALTPILZ DER GRÜNEN BEWEGUNG

Die Frage, ob Gentechnik eine wunderbare Verheißung moderner Molekularbiologie oder Teufelszeug ist, macht einen grundlegenden Riss durch die grüne Bewegung deutlich. Verbände wie Greenpeace, der Bund des Umwelt- und Naturschutzes, die sogenannten “Friends of the Earth” sowie mehrheitlich die Partei Bündnis 90/die Grünen sind gegen den Einsatz von genmanipuliertem Saatgut. Teile der Grünen Jugend jedoch stellen sich neuerdings auf die Seite des europäischen Bauernverbands sowie der Mehrheit der Gentechnik-Forscher, die sich für den Einsatz stark machen. Die Spaltung der Öko-Bewegung in Gegner und Befürworter der Gentechnik ist aber mehr als eine Detailfrage über das beste Vorgehen in der modernen Landwirtschaft: Hier offenbaren sich zwei Weltbilder innerhalb des ökologischen Denkens, die miteinander kollidieren und nicht vereinbar sind. Entweder nämlich, man glaubt an den technischen Fortschritt, an die Vernunftfähigkeit des Menschen und an die Findigkeit kreativen Unternehmertums oder man sieht das Leben in der Moderne als grundsätzlich negativ an, mit seiner bedrohlichen allmächtigen Technik und seiner ausgedehnten Massenproduktion. Technik oder Verzicht, wird damit zur Zukunftsfrage der jungen Generation, nicht nur in der Klimafrage. Es gibt Hoffnung, dass sich die technikfreundliche, positive Sicht auf die Moderne innerhalb der Grünen durchsetzen könnte.

Hauke Köhn von der Grünen Jugend Hannover brachte im Herbst letzten Jahres einen Antrag bei der Grünen Jugend Niedersachsen zum Erfolg, der sich für die Verwendung der Gentechnik in der Landwirtschaft ausspricht. Der Antrag fordert nichts weniger, als auf wissenschaftlicher Basis anzuerkennen, dass Gentechnik viele Vorteile für die Gesellschaft biete. Die Risiken seien hingegen überschaubar und politisch beherrschbar. Mit dieser Position ist Köhn seither nicht nur beliebt bei seinen Parteigenossen. Wie er gegenüber der “ZEIT” äußerte, habe “bei manchen Grünen-Treffen Eiseskälte geherrscht, wenn das Thema aufkam, bei anderen wurde es hitzig.” Zu tief sitzen die Vorurteile gegenüber der Gentechnik, die NGOs wie Greenpeace seit Jahren systematisch schüren.

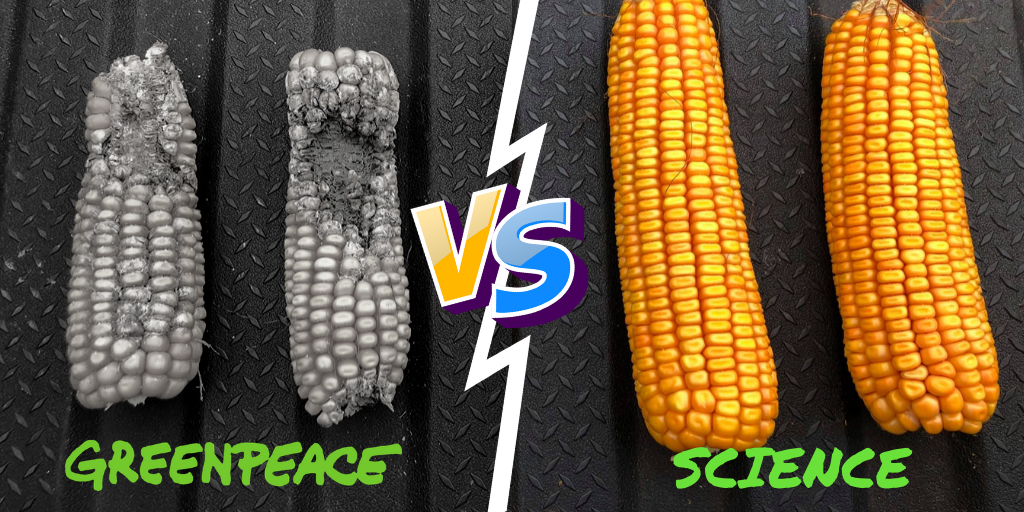

Gentechnik habe seine Versprechen „seit jeher gebrochen“, heißt es beispielsweise auf der Internetseite der grünen Friedenswächter. Durch die „Verwendung von genmanipuliertem Saatgut konnten keine Ertragssteigerungen erzielt werden und der Pestizideinsatz steigt mittelfristig sogar an“, heißt es dort. Mit der Redlichkeit dieser Aussagen nehmen es die Aktivisten wohl nicht ganz so genau. Auf den ersten Blick stimmt es zwar: In den meisten Fällen steigert der Einsatz von Gen-Mais nicht die Ernte des Maises. Aber – und das verschweigt Greenpeace seinen Anhängern lieber – es senkt die Kosten für die Maisproduktion erheblich, weil die Pflanzen resistent gegen Schädlinge sind und daher weniger Schädlingsbekämpfungsmittel eingesetzt werden müssen. Der Einsatz von genmanipuliertem Saatgut konnte bisher den Ertrag um bis zu 28% erhöhen und weitere Erfolge sind wahrscheinlich. Genau das passt Greenpeace aber nicht. In einem eigenen Dossier zu dem Thema heißt es, dass „genmanipulierte Pflanzen das Modell der industriellen Landwirtschaft zementieren, das globalen Märkten zwar Güter in großen Mengen liefert, die Weltbevölkerung aber nicht ernähren kann.“

Und genau das ist für Greenpeace des Pudels eigentlicher Kern. Die Landwirtschaft an sich ist böse, weil sie industriell und global agiert. Es stimmt: Unterernährung und Hunger wird es auch mit der Gentechnik noch geben, aber das liegt nicht an der bösen Landwirtschaft, sondern daran, dass Bürgerkriege, korrupte Regime und Unterentwicklung nicht durch Gentechnik allein behoben werden können. Nicht nur in der Frage der Agrarwirtschaft offenbart sich ein unwissenschaftliches Weltbild. Auch in der Frage der Gesundheit und der Risiken der Gentechnik bleiben viele Aktivisten faktenresistent. Greenpeace behauptet etwa in einem düsteren Untertitel zum Thema Gentechnik, dass “[d]er Einsatz der Gentechnik unkalkulierbare Risiken [birgt]. Mensch und Natur dürfen nicht zu Versuchskaninchen der Agrarkonzerne werden.” Die Wissenschaft aber konnte bisher keine dieser angeblich unkalkulierbaren Risiken ausfindig machen.

2010 gab die EU-Kommission ein Kompendium aus über 10 Jahren Forschung heraus, welches zu dem Ergebnis kommt, dass Gentechnik keine nachweisbaren Risiken für die Umwelt in sich trage. Auch in einer Bilanz des deutschen Bildungsministeriums aus dem Jahre 2014, nach 25 Jahren Forschungsarbeit und über 130 Projekten und 300 Millionen Euro geflossenem Steuergeld, heißt es dazu, “dass Gentechnik an sich keine größeren Risiken als konventionelle Methoden der Pflanzenzüchtung birgt.” Doch den Gegnern der Gentechnik können noch so viele Studien vorgelegt werden, belehren lassen sie sich trotzdem nicht.

Wie der Philosoph Stefan Blancke, von der Universität Gent, in einem Interview mit ZDF-Heute treffend feststellte, fällt die Panikmache vor der Gentechnik bei den meisten Menschen deshalb auf fruchtbaren Boden, weil sie Vorurteile und Naturbilder bedient, die uns intuitiv einleuchten, die aber, wissenschaftlich gesehen, weit vor das darwinistische Zeitalter zurückreichen. Die meisten Bürger würden zum Beispiel glauben, “dass alle Organismen eine Art universellen ‚Kern‘ besitzen. Einen ‚Kern‘, der diesen Organismus ausmacht, quasi definiert.“ Und daher würden in einer US-Studie Befragte nicht wissen, ob in eine Tomate implantierte Fisch-DNA die Tomate nach Fisch schmecken lässt. Das ist natürlich Unsinn, wussten aber weniger als 40 Prozent.

Solche Vorurteile führen dann dazu, dass sich knapp 80 Prozent der Deutschen in einer Umfrage des Umweltministeriums aus dem Jahr 2017 ohne erfindliche Gründe gegen die Gentechnik aussprechen. Wenige politische Fragen erreichen solch eindeutige Urteile der Öffentlichkeit. Was gerade bei diesem Thema besorgniserregend ist, da die meisten Befragten offensichtlich wenig bis keine Kenntnisse der Gentechnik besaßen. Zu der Angst, nicht mehr kontrollieren zu können, was wir über Geneingriffe erschaffen, komme, laut Blancke, die Angst hinzu, sich mit Mutter Natur anzulegen. Wir würden immer noch zu einem sogenannten zweckgetriebenen Denken neigen, das allen Naturereignissen eine bestimmte Absicht unterstelle. In dieser Sicht seien Pflanzen dazu da, uns zu ernähren, Regen, um die Erde zu bewässern und Gewitter, um uns zu erschrecken. Blancke dazu: „Gentechnik ist da plötzlich das Böse, das die Pläne von ‚Mutter Natur‘ durchkreuzt. Nicht umsonst gibt es den Begriff ‚Frankenfood‘. Die Botschaft ist klar: Legen wir uns mit ‚Mutter Natur‘ an, rufen wir gewaltige Katastrophen hervor.“

Es ist nur zu hoffen, dass sich die Sicht des 21-Jährigen Junggrünen Hauke Köhn in Zukunft durchsetzt, der in seinem Antrag mutig schreibt: “In jedem Fall können die pauschalen Vorwürfe, die gegenüber der grünen Gentechnik bestehen, nicht aufrechterhalten werden. Es sind durchaus ökologisch nachhaltige GVO vorstellbar, die gegenüber konventionellen Agrarpflanzen große Vorteile hegen.” Ergänzen müsste man noch, dass solche GVO (Gentechnisch veränderte Organismen) nicht nur vorstellbar sind, sondern schon täglich genutzt und weltweit gebraucht werden.

Originally published here.

The Consumer Choice Center is the consumer advocacy group supporting lifestyle freedom, innovation, privacy, science, and consumer choice. The main policy areas we focus on are digital, mobility, lifestyle & consumer goods, and health & science.

The CCC represents consumers in over 100 countries across the globe. We closely monitor regulatory trends in Ottawa, Washington, Brussels, Geneva and other hotspots of regulation and inform and activate consumers to fight for #ConsumerChoice. Learn more at consumerchoicecenter.org