European Green Deal: GMOs completely absent

Can Europe still claim to be on the side of science?…

Agriculture is one of the key strategic pillars in the fight against climate change. In a world where average temperatures are set to reach levels that humanity has never experienced, we will have to be even more resourceful to feed an ever-growing population. Unfortunately, the “Farm to Fork” plan unveiled by the European Commission last May seems to be going in the opposite direction. Instead of relying on the latest innovations brought about by genetic engineering, the Commission prefers to bet on the democratisation of organic farming, whose ecological and health virtues are, after analysis, very limited.

The Commission plans to reduce the European agricultural area by 10% while converting 25% of agricultural land to organic farming, representing only 7.5% of the land. These two objectives are incompatible. Indeed, given that the profitability per hectare of organic farming is on average 25% lower than that of conventional farming, an increase in the proportion of “organic” farming in Europe must necessarily be accompanied by an increase in the area cultivated – and potentially by a reduction in forests. For example, an article published in Nature in December 2018 showed that conversion to organic farming could lead to significant CO2 emissions by promoting deforestation. After studying the case of organic peas grown in Sweden, the authors conclude that they have “an impact on the climate about 50% greater than conventionally grown peas”.

The plan also calls for the use of chemical pesticides to be halved. Here again, the Commission fails to recognise that pesticides are essential to protect crops from disease and pests. Farmers cannot do without them without risking the decimation of their crops and the collapse of their yields – exposing consumers to shortages and sharp price fluctuations. And since they cannot do without them, if they are forbidden to use chemical pesticides, they will turn to so-called ‘natural’ pesticides, as in organic farming. However, just because a pesticide is natural does not mean that it is necessarily less dangerous for health and the environment. On the contrary, copper sulphate, a ‘natural’ fungicide widely used in organic farming, is known to be toxic.

Conversely, just because a pesticide is synthetic does not mean it is dangerous. Indeed, despite the paranoia surrounding chemical pesticides today, the European Food Safety Agency concluded in a 2016 study that they “are not likely to pose a health risk to consumers”. This is not surprising, as pesticides are tested for health effects before being put on the market.

It is true, however, that in environmental terms, chemical pesticides can have harmful consequences. But no more so than natural pesticides – copper sulphate, once again, is as toxic to humans as it is to ecosystems. So the challenge is to find a real alternative to pesticides.

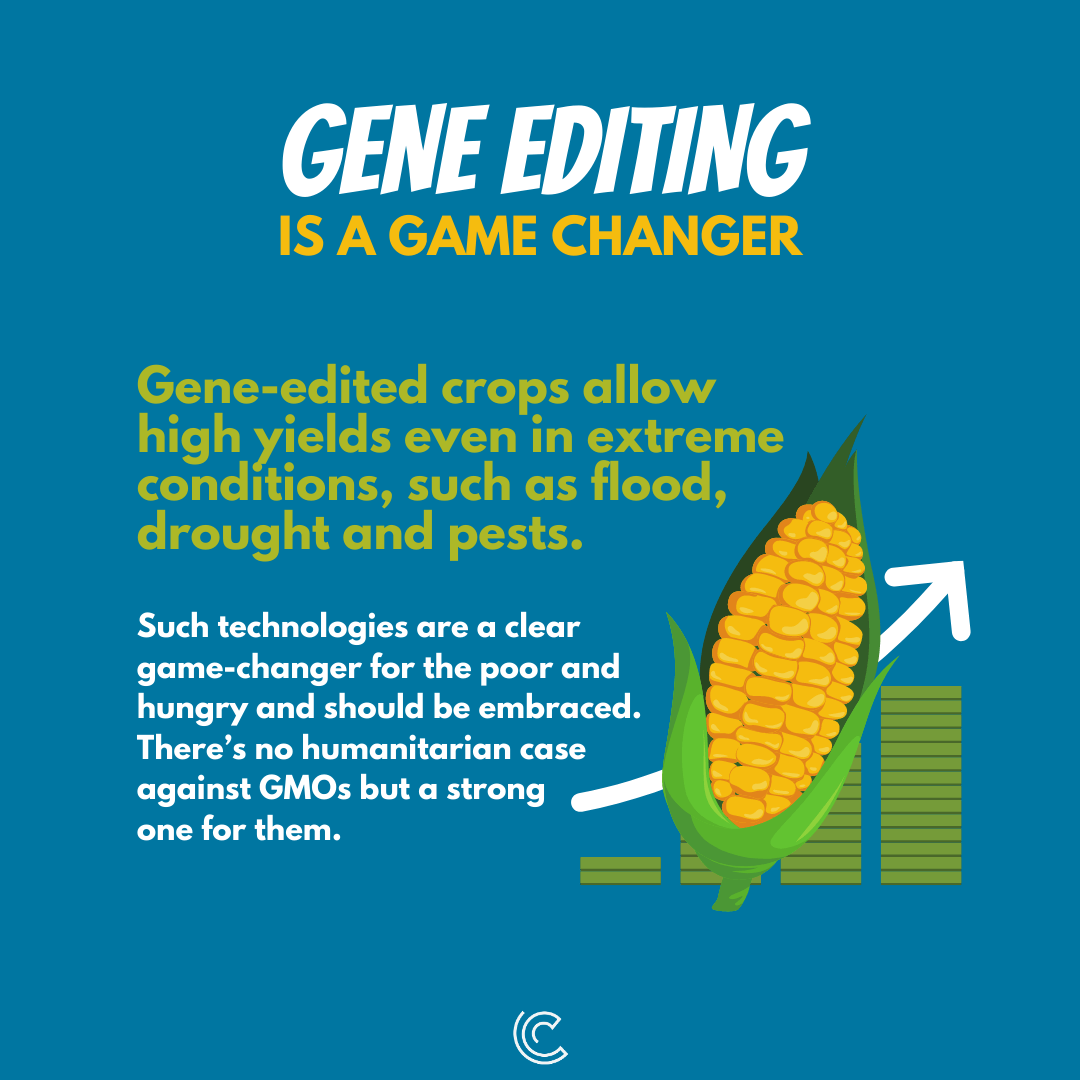

The good news is that one already exists: genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Indeed, scientists at the Georg-August University in Goettingen, Germany, have estimated that genetic engineering has already reduced the use of chemical pesticides worldwide by 37% while increasing crop yields by 22% and boosting farmers’ profits by 68%. But the benefits of growing GM crops do not stop there. It also produces drought-resistant crops and end products with improved nutritional properties. In short, genetic engineering promises to address ecological, health and demographic challenges simultaneously.

Unfortunately, the development of this technology is not part of the Commission’s plan. This is due to the precautionary dogma that inspires the current European regulations. Indeed, while much progress has been made in this field, allowing the various techniques to gain in precision, the regulation that applies to all GMOs -without distinction- has not evolved since 2001.

It is regrettable that a “Green New Deal” whose ambition is to build a “healthier and more sustainable food system” does not include a review of the rules governing the research, development and distribution of GMOs. This is all the more so because, given the current state of knowledge, there is no reason to believe that human-directed genome modification entails more risks than that which occurs naturally through the evolutionary process.

In 2016, a hundred Nobel Prize winners spoke out in favour of GM crops: “GMOs are safe, GMOs are environmentally friendly, GMOs are especially important for small farmers”. What is the logic of politics paying attention to the scientific consensus on global warming but ignoring this call from 155 Nobel Prize winners for the development of GMO agriculture? Can Europe still claim to be on the side of science?

Originally published here