Ottawa, ON: Canadians elected the Liberal Party under Prime Minister Mark Carney last night and the Consumer Choice Center congratulates them on their victory. The CCC will continue to promote...

Kuala Lumpur, 24 April 2025 — In response to the Deputy Inspector-General of Police’s recent call for state-level bans on vaping, Tarmizi Anuwar, Malaysia’s representative of the Consumer Choice Center...

A surge in downloads for an encrypted messaging app raises questions about growing concerns around data privacy and digital surveillance in the US. In this video, Yaël Ossowski from CCC...

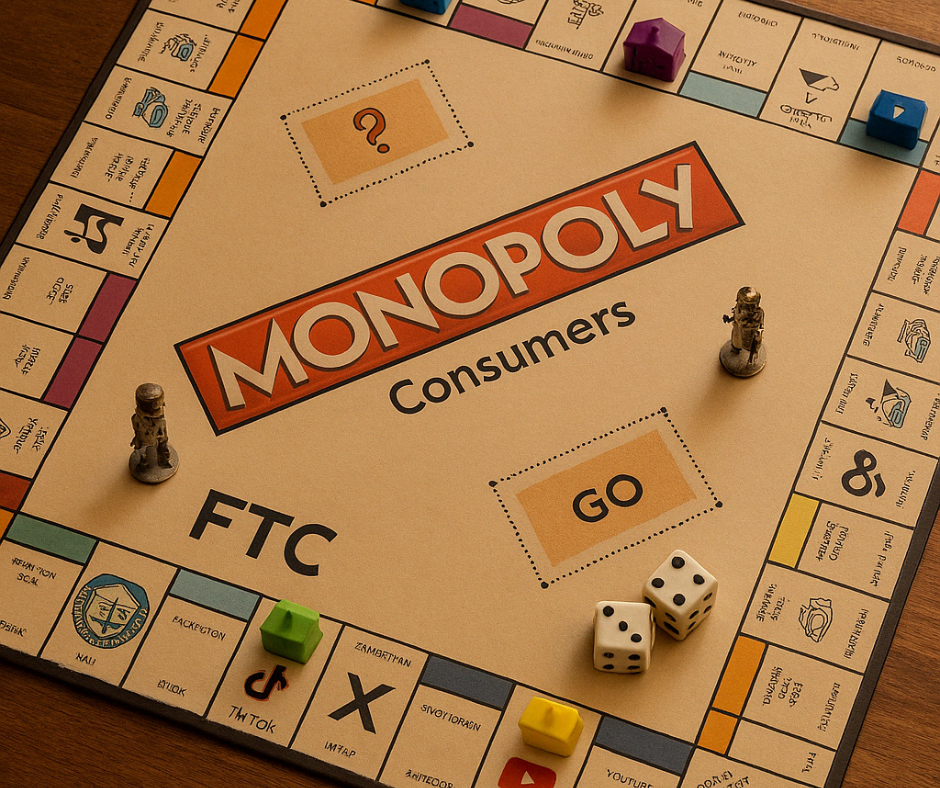

Meta had its first day in court against the Federal Trade Commission in what will be the second-largest antitrust trial of the decade. At stake is Meta’s ownership of both Instagram and...

THERE IS (STILL) NO SOCIAL MEDIA MONOPOLY WASHINGTON, D.C. – Meta stands down the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) today in the most critical antitrust trial in the history of Mark Zuckerberg’s powerhouse...

Bagi banyak orang Indonesia, Bahasa Jepang merupakan salah satu bahasa yang cenderung cukup sulit dipelajari. Mulai dari karakternya yang sangat banyak dan jauh berbeda dengan karakter latin, cara baca, pelafalan,...

India’s decision to withdraw the 6 per cent equalization levy, also known as the “Google Tax” marks a paradigm shift in the nation’s approach to digital taxation. India’s decision to...

En pleine croisade contre la vie privée numérique, ce scandale révèle une hypocrisie politique profonde et relance le débat sur le droit au secret des correspondances pour tous. Dans un...

Californians are overall accepting of Gov. Newsom’s policies and the kind of restrictions being targeted by Congressman Kiley, but at no time did the rest of us agree to live...

Liberal leader Mark Carney wants Canadians to believe he’s bringing the Grits back to the centre after a decade of the party running to the left. That’s why he’s talking...

As economic tensions and regulatory fragmentation deepen between the United States and the European Union, finding constructive pathways for cooperation has become more urgent than ever. A recent policy paper...

If we knew about a $500 billion drain on the American economy that inflates prices for everyday consumers, slows down much needed technological innovation, and locks real victims out of...