Sustainable Agriculture

Challenges and opportunities for a 21st-century food system

From every available perspective, humanity has managed the phenomenal task of making food safer, more available, and more affordable over many centuries. Through agricultural intensification and modern machinery, innovation has catapulted most nations from peasant farming to the comforts of the modern world. Visiting a farm today leaves one mesmerised by the sheer amount of technological progress that would have been unfathomable for our ancestors.

But with new opportunities come new challenges. Climate change, as well as a political shift to more environment-conscious decision-making, has shifted the question of farming from “what” we produce to “how” we produce. Agriculture is at the centre-stage of a battle of ideas and political roadmaps, all too often moving away from the needs of farmers and consumers, and into the realm of ideology. It is getting harder to argue for evidence-based policy-making.

The European Union wants to create a sustainable food system, however, policy decisions at both the European and member state level have consistently lacked coordination. Europe is behind on innovation when it comes to new agricultural technology, while steadily phasing-out crop protection tools. Organic farming is becoming increasingly incentivised by public policy.

This policy paper explores the challenges of defining what sustainable agriculture should look like while dispelling many of the myths present in the debate surrounding conventional and organic farming. The Consumer Choice Center believes that we need a common base of facts and knowledge, and we must strive to work together to create the best system for farmers and consumers alike.

Hazard vs Risk

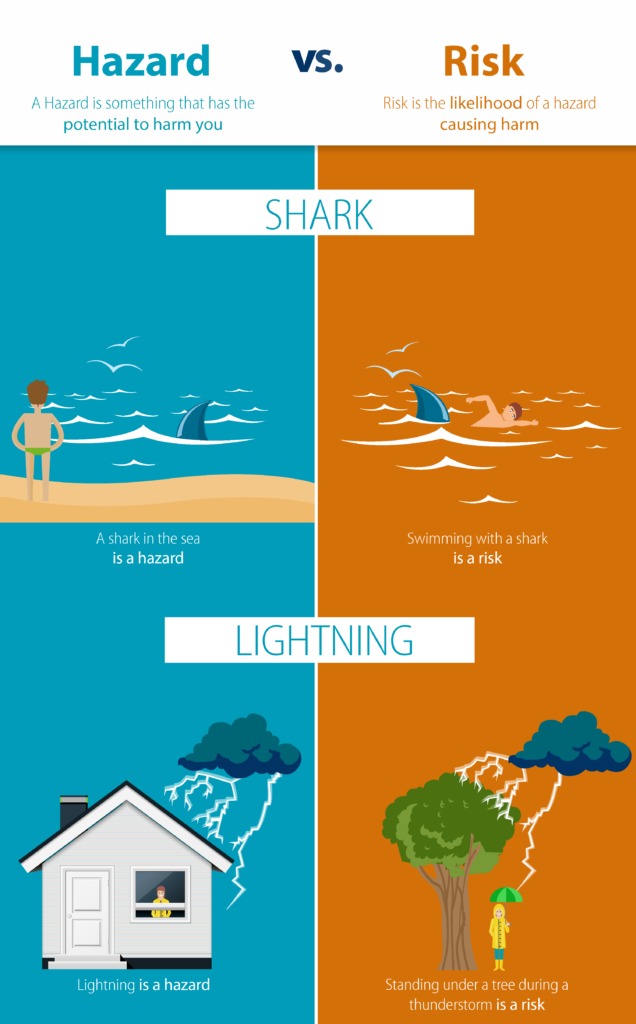

Risk-based regulation manages exposure to hazards. For instance, the sun is a hazard when going to the beach, yet sunlight enables the body’s production of vitamin D and some exposure to it is essential to human health. As with everything else, it is the amount of exposure that matters. A hazard-based regulatory approach to sunlight would shut us all indoors and ban all beach excursions, rather than caution beach-goers to limit their exposure by applying sunscreen. The end result would be to harm, not protect human health. The same logic of hazard-based regulation is all too often applied in crop protection regulation, where it creates equally absurd inconsistencies. For instance, if wine was sprayed on vineyards as a pesticide, it would have to be banned under EU law, as alcohol is a known and quite potent carcinogen at high levels of consumption.

All this is rationalized through an inconsistent and distorted application of the precautionary principle. In essence, hazard-based regulation advocates would endorse outlawing all crop protection methods that cannot be proven completely safe at any level, no matter how unrealistic — a standard which, if applied consistently, would outlaw every organic food, every life-saving drug, and indeed every natural and synthetic substance. By ignoring the importance of the equation Risk = Hazard x Exposure, hazard-based regulation does not follow a scientifically sound policy-making approach.

Credit: European Food and Safety Authority.

A number of civil society campaigning groups have set out to reduce the total amount of crop protection tools, all too often for ideological reasons. In that process, certain actors have chosen to misinform consumers about the nature of chemical compounds, or their effect on insects, soil quality, or human health.

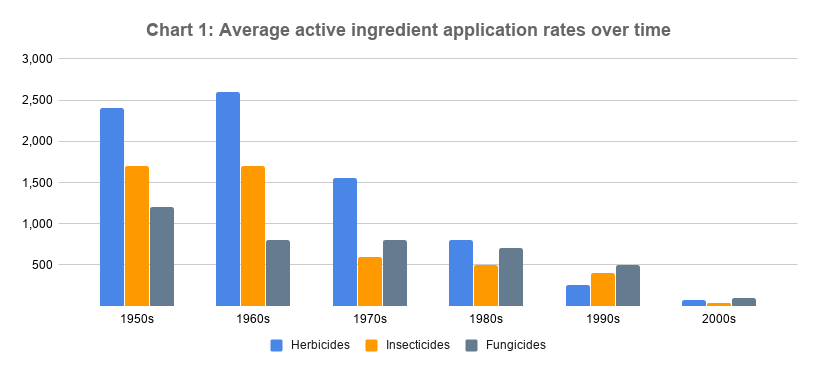

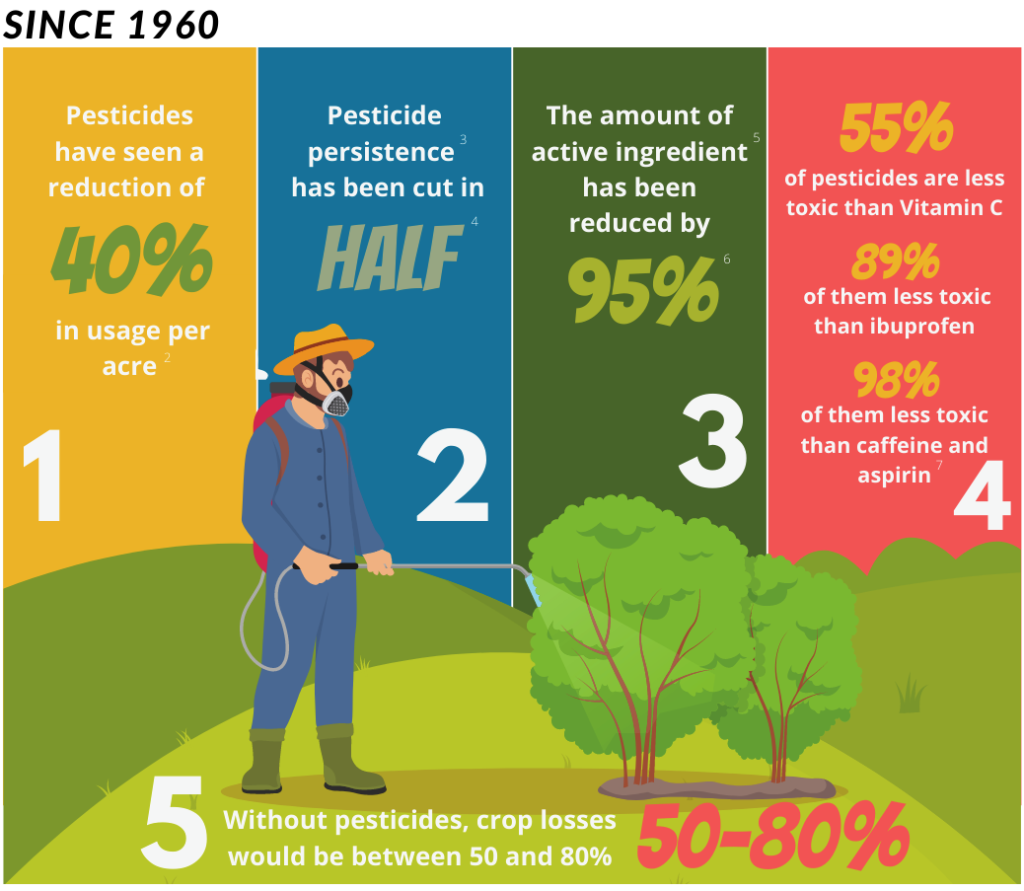

In order to set the record straight, we would like to outline a number of facts:

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), farmers globally would lose 30 to 40 per cent of their crops due to pests and diseases. The importance of crop protection is thereby emphasised, however, it is equally important to address the chemical approval process that guides food safety in Europe.

We would like to emphasize that we believe in the integrity of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), to determine the safety of a crop protection tool. However, this has not been a shared feeling within the European Union’s institutions. The European Parliament has cast doubt on the scientific integrity of EFSA, particularly as it related to the approval of the herbicide compound glyphosate. In 2017, EFSA was forced to respond to allegations of conflict of interest that had not been substantiated. It writes in its response: “The review papers in question [those suspected of having been influenced by the manufacturer] represented only two of approximately 700 scientific references in the area of mammalian toxicology considered by EFSA in the glyphosate assessment.”

The European Parliament subsequently created the Special Committee on the Union’s authorisation procedure for pesticides (PEST), which further questioned the integrity of EFSA, and has cast a shadow over the work of EFSA and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), in a report released in 2018.

Scientific facts should not be subject to political interpretation. The scientific method is supposed to be a means of acquiring knowledge that adapts to the introduction of new information. Political institutions need to be careful not to create an environment in which food safety assessments favourable to the political majority are approved, while those rejecting the premises of the political majority are investigated.