Last month, we finally saw the introduction of a comprehensive US bill to offer a legal pathway for digitally issued stablecoins, cryptocurrencies on open blockchains kept at parity with the US dollar.

The bill was introduced by Sens. Cynthia Lummis (R-WY) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), named the Lummis-Gillibrand Payment Stablecoin Act.

The bill outlines various measures for recognizing the value of stablecoin networks, as well as the various custodial services that would be required.

The existing market for stablecoins is already rich and highly competitive, with various tokens like Tether, DAI, and USDC launched on various blockchains, from Ethereum to TRON, Polygon and Solana. And all this exists, at least in the United States, without any framework for regulation.

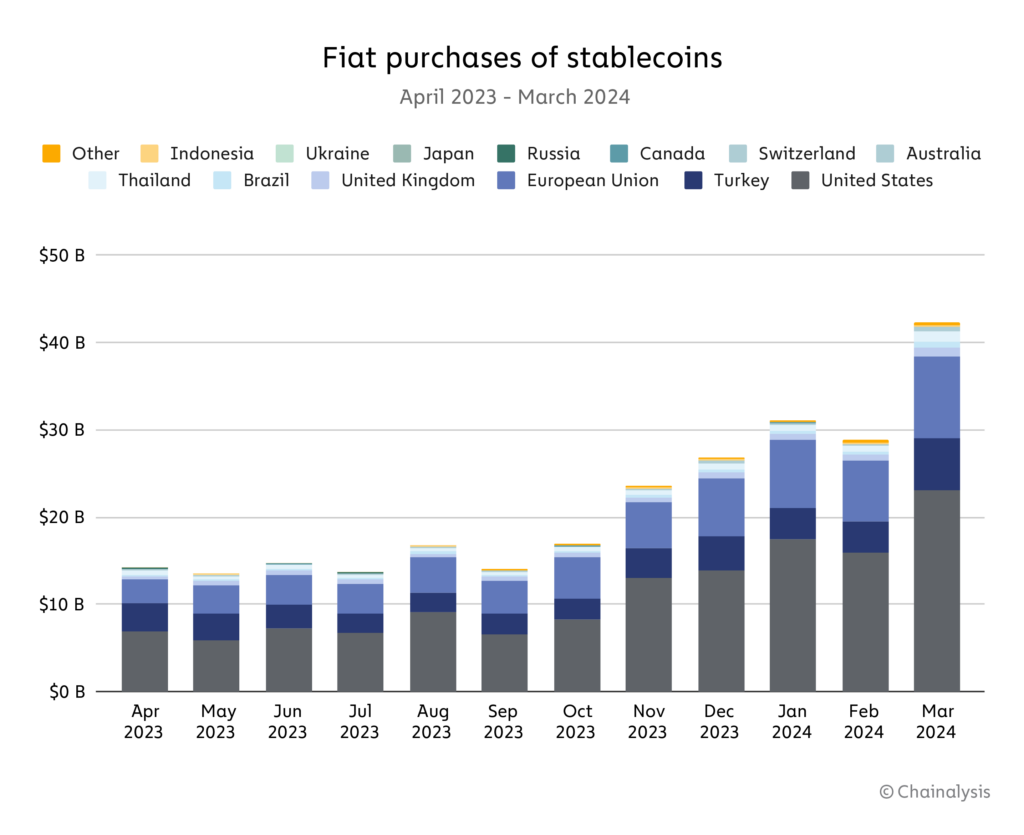

Globally, stablecoins have become a necessary part of safeguarding wealth from rapidly inflating currencies, used widely across the EU, Turkey, Argentina, and across southeast Asia.

In the last 30 days alone, there have been over $2.4 trillion worth of transactions using stablecoins, used by over 26 million people across the globe. There are more than $146 billion in value locked into these tokens, according to the Visa On-Chain Analytics.

Even though Americans are using stablecoins in large numbers, the lack of regulatory certainty and the complications with on and off ramps mean many new stablecoin issuers are wary of offering services in the United States.

As such, the Lummis-Gillibrand Act is an important bill to read through, both for its advantages, but also its very serious shortfalls.

What’s to like:

It’s a starting point.

The uncertainty around stablecoins leaves them much more the payment of choice in decentralized markets and in decentralized finance, keeping them far away from the traditional banking system.

This bill, whatever anyone might say, at least opens the conversations and allows us to understand how future legislation can be crafted. In the waning days of this Congress, it’s uncertain it’ll be passed, but it’s a good shot.

It requires full reserves.

Today’s stablecoins compete based on both their utility and the health of their reserves. That lawmakers see this is important, but seems exceedingly stringent considering the realities of traditional banks. This contrasts with the US fiat banking system, where banks are currently held to a reserve requirement of 0%. If the trade-off for allowing stablecoins is full reserve issuers, I think most consumer would agree this is likely a good thing. Ideally, though, stablecoins would be allowed to compete as payment rails with the same rules as traditional banks. But I think that is likely too far gone.

Custodians will be strictly regulated

As we’d expect, custodians of the reserves of stablecoins would be held to stringent rules. There could be no rug pulls, funny tricks, or fradulent accounting. That’s probably a good thing.

It aims to preserve the US’ unique dual banking system shared between the states and the federal government.

The bill recognizes the unique decentralized nature of the US banking system, empowering states and their institutions to oversee FinTech and banking institutions. The ability for non-depository trust companies to issue stablecoins would be game-changing. However, it does give veto power to the Federal Reserve, which almost makes the effort moot.

What’s not to like:

The Federal Reserve has ultimate veto power.

In a system where private stablecoins would be allowed to exist, we would expect that the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, would do everything to oppose them, as they have. Granting the Fed veto power means likely that no stablecoins would ever be approved.

As Cato Institute scholars Jack Soloweyand Jennifer Schulp argue in Coindesk, the ability for the Fed to block any digitally-based “competitors” would surely be a death knell.

The ceiling on reserves limits the potential for innovation and growth.

The bill outlines a $10 billion cap for state trust companies that want to issue a stablecoin, meaning the total liquidity a stablecoin would be allowed to have would barely rank among the top 150 banks in terms of assets, and significantly kneecap the ability for a stablecoin protocol to innovate, be profitable, and reach large numbers of customers and holders.

These stringent rules would likely mean that only one stablecoin could potentially exist.

The way this bill is written, the only conceivable candidate to be a legal stablecoin, that would have the resources to be issued by a state trust company, would be USDC owned by the firm Circle. This would technically make all other stablecoins used by Americans illegal.

CONCLUSION

It’s obvious that there is high demand for a digital stablecoin based on the US dollar. With such a high volume and number of daily transactions, there are already hundreds of millions of people using these for both savings and spending.

The Lummis-Gillibrand bill makes a good first effort at paving a way for legalizing stablecoins, but unfortunately grants too much veto power to the Fed, caps the innovation and reserves these coins could have, and ultimately means we would be no closer to a system that both recognizes the utility of stablecoins while allowing ordinary people to use them.