America’s credit markets are the envy of the world. Unlike many other countries in the world, millions of American consumers, especially those in modest-income households, have access to flexible financial tools that smooth day-to-day spending, handle emergencies when they arise, and allow consumers to achieve higher living standards. The average American today has instant access to nearly $30,000 in credit to finance purchases and payments.

While credit cards and credit options are a part of American life, that also includes consumer debt. According to the Federal Reserve, the average US household carries a credit card balance of $6,523, while the latest average interest rate is 21.4% APR. Globally, Americans rank near the middle of the 35 OECD countries in terms of total household debt as a percentage of income.

The causes for this are varied but still concerning. While Americans are much wealthier and less indebted than those in comparable industrialized countries, carrying a balance still provides a significant strain on families.

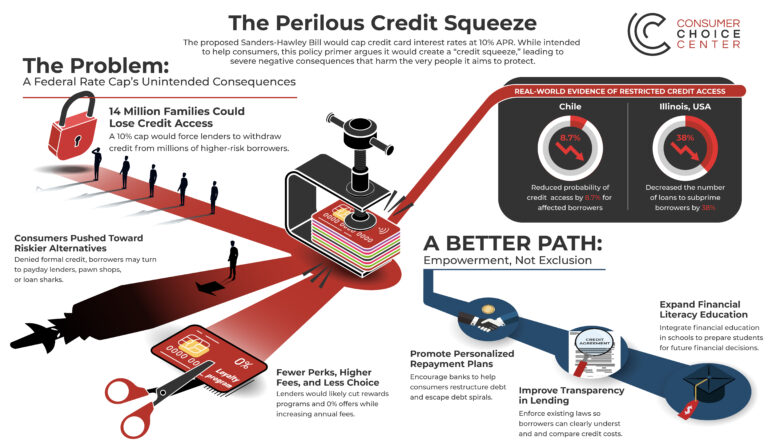

As a response, some legislators propose a one-size-fits-all fix to limit growing consumer debt. The proposed Sanders-Hawley Credit Card Interest Rate Cap Bill would impose a strict federally mandated annual percentage rate (APR) cap of 10%, nearly half the current market rate.

*Following their lead, on January 9th, 2025, President Donald Trump posted to this Truth Social account that he will rush this policy into force. “Effective January 20, 2026, I, as President of the United States, am calling for a one year cap on Credit Card Interest Rates of 10%,” wrote Trump.

Many states enforce usury laws that limit interest rates on credit products, but due to the nation’s unique dual-banking system split between federal and state regulation, most providers issue credit from more banking-friendly states.

Turning to the federal level, this policy primer will examine the social and economic costs of the proposed cap and suggest alternative solutions to addressing credit card debt and providing access to credit for millions of Americans who need it.

Credit cards provide unsecured, flexible borrowing that millions of families depend on for groceries, utilities, medical bills, and unforeseen emergencies. Because this access comes without collateral and allows borrowers to draw credit instantly up to their limit, credit cards carry more risk for lenders than mortgages or auto loans, which is why their interest rates are higher.

A federal 10% interest-rate cap would ignore these economic realities. Capping credit-card APRs below lenders’ risk and operating costs is a direct form of price control. As any reasonable economist knows, price controls cause shortages. For credit cards, that means less access to credit, fewer card options, and the elimination of rewards programs and 0% promotional offers that many consumers count on.

In the market system, interest rates are set by pricing in fraud and servicing costs, the consumer credit risk, operational expenses of credit providers, and the funding of rewards and promotional offers that many consumers take advantage of when they use their cards. Rates vary by consumer based on a host of factors.

That said, however, many Americans still struggle with paying off their cards.

A 2025 poll by the financial services firm Happy Money found that 42% of Americans are concerned about credit card payments, but 21% in the same survey say they have taken no meaningful action to better manage their debt situation in the last six months.

Rather than demanding an interventionist federal solution to choke down available credit, this demonstrates a key need to address why people go into debt in the first place, and how they can best manage it with available education and tools. Enacting new laws or restrictive limits to reduce credit access to all Americans is not a reasonable solution.

Capping rates below economic reality doesn’t eliminate risk or mollify financial behaviors of consumers, but it does force banks and credit providers to withdraw credit from their customers. That would have an immediate negative impact on millions of American consumers.

Historically, policies that impose government price controls on credit severely restrict the availability of credit for everyday consumers.

One study followed the impact of Illinois’ policy to cap all borrowing and financing at 36% APR. It found that the “interest-rate cap decreased the number of loans to subprime borrowers by 38 percent and increased the average loan size to subprime borrowers by 35 percent”.

What’s more, follow-up surveys of consumers in the state found an overwhelming response suggesting that “the interest-rate cap worsened the financial well-being of many of these borrowers,” with answers to previous surveys showing that “25 percent of pawn users, 18 percent of vehicle title users, and 26 percent of payday loan users did not apply for credit in the last 12 months because of fear of rejection”.

If a 10% APR rate is enforced at the federal level, the Bank Policy Institute notes that at least 14 million US families who carry revolving card balances would be directly harmed by having their access to credit reduced.

Nearly three-quarters of higher-risk borrowers would lose card access entirely, depriving them of the necessary credit to make flexible purchases for groceries and utilities, medical bills and emergencies, and income gaps between paychecks.

Referencing consumer sentiment, a poll conducted by Morning Consult for the American Bankers Association in October 2025 found that 66% of consumers would oppose caps on interest rates if it meant the introduction of a credit card annual fee, while 64% opposed caps if it would lead to any increase in user fees.

Without the ability to price risk, lenders would be forced to reduce the scope of credit availability to consumers with more modest means, resulting in more denials instead of approvals, lower credit limits, and fewer card options for those building credit for the first time.

This policy would slam the door on upward financial mobility.

Both political and academic supporters of caps on interest rates claim to be looking out for the most vulnerable consumers. However, they ignore solid evidence that interest rate ceilings lead to the denial of credit in the first place and harm those with modest incomes by curtailing the credit options available to them.

In 2013, the country of Chile passed a law to reduce the legal maximum rate on consumer credit from 54% to 36%, focused mostly on unsecured loans, including credit cards.12 It provides the best real-world example we have of the effects of interest rate caps on consumer welfare.

The most definitive study undertaken by the Central Bank of Chile found that the cap reduced the probability of credit access for affected borrowers by about 8.7% and excluded roughly 9.7% of previous borrowers from the formal consumer-loan market altogether.

An additional paper by Jose Ignacio Cuesta and Alberto Sepulveda published in 2019 found that the rate cap reduced the amount of lending to mostly poor consumers by almost 20%.

“We find that the trade-off between consumer protection and credit access exists, but that adverse effects on credit access dominate consumer protection effects. Thus, while the objective of interest rate regulation is often to protect borrowers from bank market power, we find it ends up mostly harming borrowers’ access to credit,” write the authors.

The Chilean case underscores a fundamental truth of credit markets: price controls may lower the headline cost of borrowing, but they also destroy the very access that makes credit cards valuable — particularly for households with volatile income or thin credit histories.

The most cited academic contribution on proposals to mandate a cap on credit card interest rates was produced by Vanderbilt University’s Policy Accelerator program in September 2025.

Their argument rests on the supposed high profit margins of credit card issuers alone, which the researchers argue would be large enough to absorb and even offset the impact of less revenue from interest.

In their view, the economic impact of capping interest rates on credit cards would only be marginal, forcing credit issuers to seek profits elsewhere and passing savings on to consumers. “The profit margins of the credit card market at every FICO tier are thick enough to absorb a very significant reduction in interest caused by a new federal usury rate,” write the researchers.

In the model created by the researchers, a 10% APR cap as proposed in the Sanders-Hawley bill would allow customers to save nearly $100 billion in interest payments while credit providers would be forced to reduce benefits to customers by $27 billion, mostly those with less creditworthiness.

As the researchers themselves state, this “would not generate enough returns to be viable” and “the industry would need to adjust”. “Banks could find efficiencies and cut marketing costs,” they state, demonstrating that such a drastic rate cap would have an immediate impact on low-income consumers who are more desperate for credit.

This line of argumentation, as well as their entire economic model, fails to comprehend credit markets themselves, let alone the costs and risks of operating a financial company. Credit cards are unsecured, high-risk products priced according to borrower risk, fraud exposure, and operational cost. Mandating piecemeal changes to business models will not somehow elicit millions more that companies are free to disperse or pass on to customers.

The paper’s assumption that bank and credit providers would simply slash marketing or rewards instead of tightening credit access contradicts decades of empirical evidence, including the experience in Illinois and Chile (mentioned above), where interest-rate ceilings led to double-digit reductions in loan access and measurable declines in borrower financial well-being.

In practice, a 10% credit-card cap would slam the door shut on at least 14 million Americans, particularly those with modest incomes who rely on revolving credit for everyday necessities.

In the current competitive credit card market, many consumers take advantage of several promotions and benefits. These include 0% APR balance transfer promotions, cash back and travel rewards programs, no foreign transaction fees, and no-annual-fee credit cards.

These programs and benefits exist because lenders can cross-subsidize them with regulated, risk-based interest pricing that allows them to offer these advantages while remaining profitable. This is a net positive to Americans who use them.

However, in imposing a federal cap on interest rates and the ability for lenders to recoup their costs, it would necessarily distort the market and most likely lead to the dramatic shrinking and restricting of rewards programs, reduce the number of 0% introductory offers, and likely cause annual fees and service charges to have to rise to make up the difference.

In other words, such a cap would lead to fewer perks, fewer choices, and worse products for American credit consumers.

When riskier borrowers who are more low-income are locked out from credit cards due to caps on interest rates and their inability to access them, it is only natural that they will seek credit elsewhere.

This could include payday lenders, pawn shops, rent-to-own schemes, and unregulated loan sharks, where interest rates can be astonishingly high and terms are much less forgiving and flexible than traditional creditors.

Rather than impose sweeping federal caps that would cut off access to credit for millions of consumers, policymakers have additional options at their disposal.

The Sanders-Hawley credit-card interest-rate cap, while well-intended, fails to consider the negative externalities that would result from choking off certain Americans’ access to credit tools.

An artificially low cap on credit card interest rates would restrict access to credit for high-risk and lower-income borrowers, increase consumer costs through fees and loss of rewards, push borrowers toward inferior and riskier lending alternatives, and decrease overall consumer welfare, especially among vulnerable families.

Rather than restrict the lending rates offered by credit firms that would hurt consumers’ access to credit, Congress should promote choice, affordability, and inclusion.

Deputy Director