At first glance, the 340B program sounds simple. Certain hospitals and clinics can buy medicines at much lower prices. The idea is that these lower prices help them support patients who need extra help.

However, the story does not end there.

The program has grown much larger and more complicated than it was originally designed to be. Today it involves many pharmacies, many different ways of shipping and dispensing medicines, and a large industry of middlemen whose business depends on processing more 340B activity. When a program gets this large, weak controls stop being a technical issue and start becoming a real financial and policy problem.

The core issue in plain language

The biggest flaw is this: In the current setup, the decision about whether a prescription qualifies for the 340B price is often made after the medicine is already given to the patient.

This is important because the lower 340B price is supposed to be limited to specific situations. The rules say a hospital or clinic should not use the discount for people who are not truly their patients. The rules also say a drug company should not be forced to give two discounts on the same prescription through different government or insurance discount programs.

But when eligibility is decided after the fact, and the hospital or clinic is the one making the decision, it becomes very hard for drug companies to confirm what is valid before money changes hands.

Why the current system can hide mistakes and abuse

Here is what often happens today: A pharmacy gives the medicine to the patient and sends the bill to the insurance plan.

Later, a hospital or clinic, often through a hired administrator, decides whether that prescription will be counted as a 340B prescription.

If they label it as 340B, the drug company ends up paying back the discount through a behind-the-scenes payment process.

The key problem is that the drug company usually does not get enough detail about the specific prescription to check whether it truly qualifies. So the system relies on trust and clean up later rather than checking first.

Why double discounts happen so often

Double discounts are not rare. They are a predictable outcome of messy timing.

Different parts of the system run on different clocks.

The prescription is filled today.

The insurance payment happens today or soon after.

Another discount request might happen later through a separate channel.

The decision to label the prescription as 340B might happen later still.

Because these steps are disconnected, it becomes possible for the same prescription to trigger both the 340B discount and another discount that the drug company has to pay. Even if people are acting in good faith, the system makes it easy for this to happen.

Why the usual fixes do not solve it

Some people point to tools like billing tags, clearing services, or audits.

The issue is that most of these happen after the discount has already been given.

They can sometimes detect problems later, but they do not consistently prevent them before the discount is applied. When the program is very large, fixing things later is not enough.

What a rebate model changes

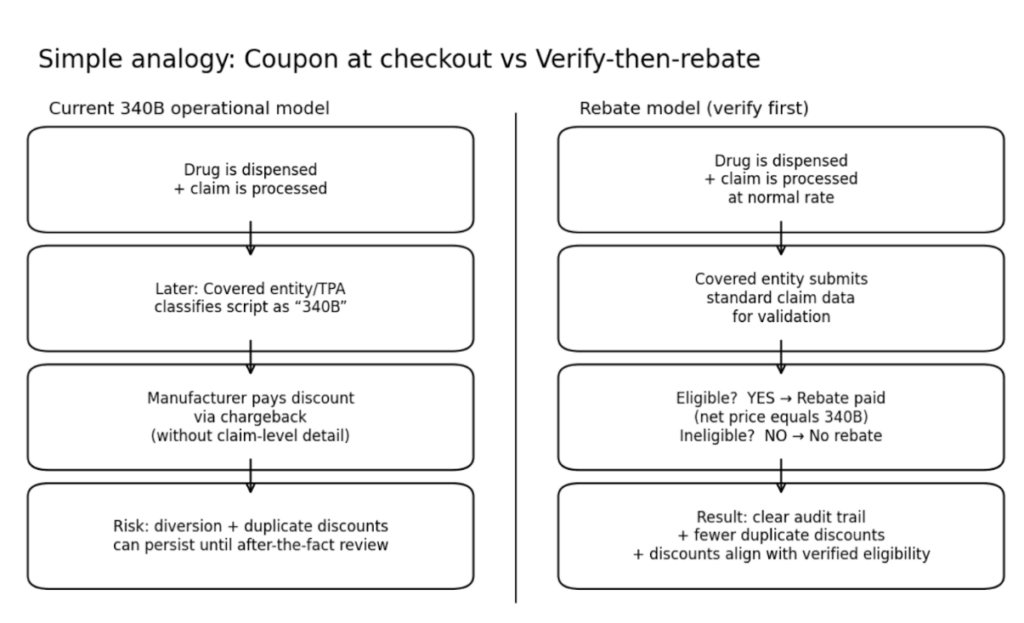

A rebate model simply changes the order of operations.

Instead of giving the discounted price first and checking later, you check first and then pay the discount only when it is proven to be eligible.

Here is the flow

Step one

The pharmacy dispenses the medicine and the insurance claim is processed at the normal negotiated price. No 340B discount is applied at the pharmacy counter.

Step two

The hospital or clinic submits the details of the prescription through a standard system. Those details are used to confirm that the prescription meets the 340B rules.

This includes confirming that the patient truly qualifies, that the prescription falls within the hospital or clinic’s eligible care, and that the prescription is not already triggering another discount that would create a double discount.

Step three

If the prescription is eligible, the drug company pays a rebate so the final net price matches the 340B price. If the prescription is not eligible, the rebate is denied and the reason is documented.

The main benefit is that the discount is tied to verified eligibility, not assumptions. In an ideal world, the discount would end up with the patient and not just stay with the administering healthcare provider.

Does this create new burdens?

Many people assume it would. In practice, it is usually a timing change more than a brand-new burden.

Hospitals and clinics already buy medicines using short-term payment terms through drug wholesalers. They already reconcile prescriptions after they happen, because that is how much of the current 340B inventory process works. A rebate model changes when the savings are delivered, not whether savings exist.

On the administrative side, the needed information already exists. Pharmacies and insurance plans already generate prescription and claim data. The rebate model standardizes how that data is shared so eligibility can be checked before the discount is paid.

Bottom line

The current 340B operating model was not built for today’s scale and complexity. A rebate model keeps the benefit but adds a basic safeguard that the current system often lacks.

Verify the prescription qualifies first. Then pay the discount. Ultimately, patients should benefit from the discount and not the profit and loss statement of a hospital that knows how to game the system.