Because so much of the U.S. healthcare system is focused on medical expenses, benefits, and insurance programs, it’s an unfortunate fact that dental care is often neglected.

An estimated 35.6 percent of U.S. adults didn’t visit a dentist last year, along with 55.3 percent of Medicaid-eligible children.

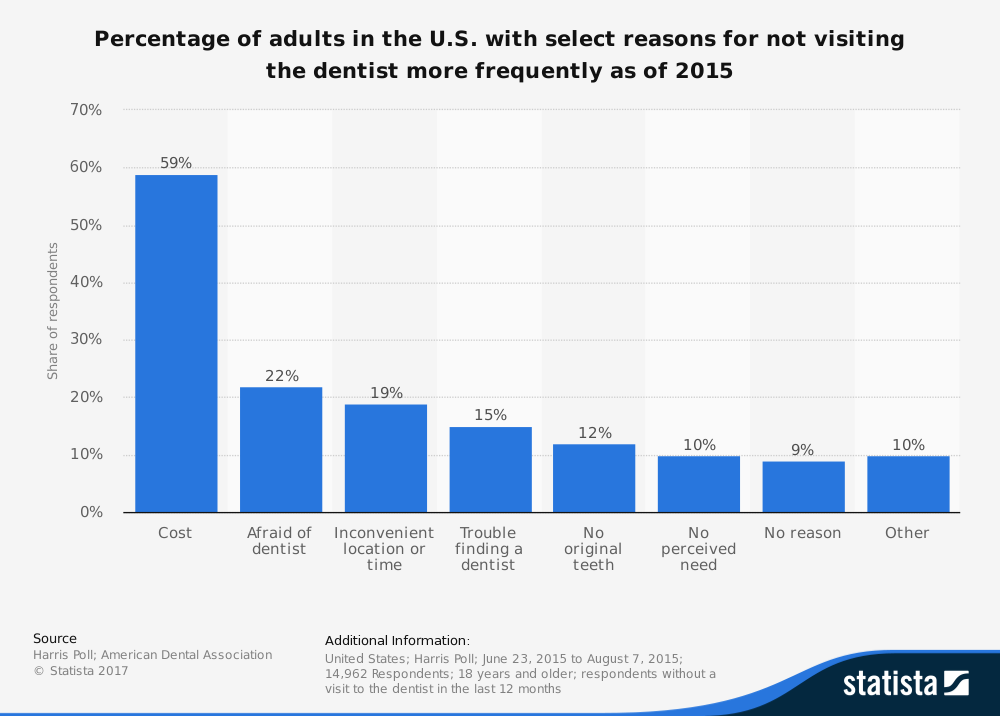

Is it mostly because people cannot find enough dentists or because costs are too high?

For consumers, it seems the single biggest reason for not visiting a dentist is cost. Knowing these facts, what can we do in order to help reduce costs for dental patients around the country? It’s a serious question which invites a good amount of discussion and recommendations.

In Florida, legislators and dental professionals have called for the state to improve the dental workforce by establishing a special loan program for dentists who practice in high-need areas.

That would at least increase the number of dentists and ease the burden for dental students who face an average amount of $287,331 in debt once they leave school.

In states like New Mexico, Arizona, and Florida, there is a movement afoot to introduce a new professional category in the field of dental care, known as dental therapists.

Dental therapists, unlike dentists, require less training and education, and could presumably offer their services at a lower cost, albeit while not fully capable of performing more complex procedures.

Such programs have already been implemented in states such as Maine, Vermont, and Minnesota, and in countries like New Zealand and Canada, but the results haven’t been clear.

New Zealand first implemented dental therapy programs early in the 20th century, and they formalized their degree program in 1999.

In the last two decades, however, the rate of child tooth decay has increased wildly, forcing thousands of children to face hospitalization or emergy surgeries. The number of children hospitalized for dental issues has skyrocketed from 4500 to 7500 in the past 15 years. So that result doesn’t seem positive.

One researcher at the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota studying this issue is very skeptical it will work in that state.

However, the reality is that this hasn’t truly addressed the problem of that growing disparity between rural and urban oral health. As of December 2016, there were only 63 licensed dental therapists, half of whom were practicing in the Twin Cities metropolitan area.

It seems that dental therapy school graduates, once able to practice, are flocking to major cities in order to pay off their debts as well.

Organizations such as Pew Charitable Trust have crafted multi-state campaigns in order to advocate for the midlevel dental position, advocating for legislation which would allow dental therapists to become legal professions and be eligible for accepting Medicaid funding.

And that last distinction is important to note.

If we look at the state of Arizona, for example, there are 1,921,145 Arizonians on the Medicaid program, according to the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. That’s 27 percent of the population eligible to have dental treatments covered as part of their public plans paid by taxpayers.

If dental therapists become a category of dental professionals and are able to perform dental services, they will also be eligible to accept Medicaid funding.

Would consumers benefit from such a scenario? Would patients be able to afford better care and have access to higher quality dental services?

That much is unclear, but the numbers from states and countries which have implemented dental therapy programs give us pause on whether they have been effective.